After a very long hiatus Zayde’s Turntable is back! We return with an older record from one of the most prolific record companies in history: Columbia. I’ve already posted about the history of Columbia elsewhere, so I won’t delve much into it here. This record, in a way, ties together some important figures in the earliest jazz recordings and…Holst!

This series is from the Columbia Graphophone Company (not a typo): “Beginning at A1 (10”) and A5000 (12”) the early couplings [on the Columbia A-series] were often wildly inappropriate, sometimes pairing comic songs with concert band selections or vaudeville routines with Victorian sentimental ballads… In early 1916, Columbia’s manufacturing branch…was reorganized as the Columbia Graphophone Manufacturing Company of Bridgeport, Connecticut and New York.” (from Allan Sutton’s 1994 Directory of American disc record brands and manufacturers 1891-1943) Actual manufacturing was done at the Howe factory in Bridgeport, most famous for creating Elias Howe’s sewing machines.

Elias Howe’s factory, most famous for manufacturing sewing machines, was also home to the Columbia Graphophone company.

How “wildly inappropriate” were the pairings? Consider the records immediately surrounding this album (A-1485) in the Columbia catalog. A-1484 offered Eddie Morton singing “While They Were Dancing Around” and Al Campbell and Henry Burr doing a duet version of “I’m On My Way To Mandalay” – and A-1486 carried two harp and zither tracks, one of Offenbach’s “La Belle Helene” and the other Karl Millocher’s “I And My Boy.”

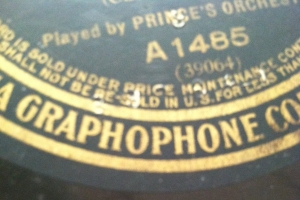

This album is in Good condition. It has some light wear and scratches on both sides, but there is no effect on the recorded audio, and the B-side label shows some soiling. It is an acoustically recorded 10-inch diameter 78-RPM black vinyl disc with lateral grooves and a ¼” spindle hole. The record catalog number is Columbia Record A-1485 and the master number is 39064/38997. It bears a stamped number “51” in the end gap on the A-side. Columbia records after 1924 had a three part code stamped in the same place to indicate the stamper and mother number used to press the record, but as this record pre-dates that practice I am not entirely certain to what “51” refers. If it were a stamper number, it could suggest that as many as 51,000 copies of the record were pressed.

This album is in Good condition. It has some light wear and scratches on both sides, but there is no effect on the recorded audio, and the B-side label shows some soiling. It is an acoustically recorded 10-inch diameter 78-RPM black vinyl disc with lateral grooves and a ¼” spindle hole. The record catalog number is Columbia Record A-1485 and the master number is 39064/38997. It bears a stamped number “51” in the end gap on the A-side. Columbia records after 1924 had a three part code stamped in the same place to indicate the stamper and mother number used to press the record, but as this record pre-dates that practice I am not entirely certain to what “51” refers. If it were a stamper number, it could suggest that as many as 51,000 copies of the record were pressed.

The top label is an example of a 1910s Columbia Graphophone record and the bottom is ca. 1919/early 1920s. The top one is clearly the same as this album, suggesting the 1913 date – not the 1919 date – is correct.

The A-side recording features Prince’s Orchestra led by Charles Adams Prince (1869–1937) playing “Babbling Brook” by Charles W. Rega (?). It runs 3 minutes and 26 seconds. The B-side recording features Prince’s Band, again led by Prince, playing the gavotte “The Village Belles” by Eduard Holst (yes, Eduard) (1843-1899). It runs 3 minutes and 5 seconds. The A-side was recorded in August 1913 and the B-side in October 1913 (Tim Brooks’ Columbia Master Book Discography lists the recording date as August 16, 1919, which does not seem likely as the Columbia A1000s series was produced between 1911 and 1913; a 1919 recording would show a catalog number in the A2500s). Les Docks sets the value at $3-$5. I could find no other current listings of this album for sale online.

If the Columbia Graphophone Company didn’t come onto the scene until 1916, how come the 1913 recording year? My guess is this album carries two tracks that may have been previously recorded and issued on another label in the Columbia family. Many of Prince’s instrumental recordings also appeared anonymously on the affiliated Climax and Oxford labels. This is purely speculation, however, as I could find no reference to either of these pieces existing on any other record besides Columbia A-1485 (the always helpful Online Discography does not have a directory of Climax records and their listing of Oxford albums shows no recording with either of these titles – except Oxford 5600A, a recording of “Village Belles,” however the composer is not Holst but Edwin F. Kendall, a piano composer better known for his ragtime pieces). Another possibility would be that this record is actually from the British branch of Columbia, confusingly also named The Columbia Graphophone Company. I don’t think this is the case for two reasons: first, the British company wasn’t founded until 1922. Second, the record bears a price that is clearly American: “65c”. Both the cost and the currency are consistent with the American record company.

If the Columbia Graphophone Company didn’t come onto the scene until 1916, how come the 1913 recording year? My guess is this album carries two tracks that may have been previously recorded and issued on another label in the Columbia family. Many of Prince’s instrumental recordings also appeared anonymously on the affiliated Climax and Oxford labels. This is purely speculation, however, as I could find no reference to either of these pieces existing on any other record besides Columbia A-1485 (the always helpful Online Discography does not have a directory of Climax records and their listing of Oxford albums shows no recording with either of these titles – except Oxford 5600A, a recording of “Village Belles,” however the composer is not Holst but Edwin F. Kendall, a piano composer better known for his ragtime pieces). Another possibility would be that this record is actually from the British branch of Columbia, confusingly also named The Columbia Graphophone Company. I don’t think this is the case for two reasons: first, the British company wasn’t founded until 1922. Second, the record bears a price that is clearly American: “65c”. Both the cost and the currency are consistent with the American record company.

The 65-cent price is visible in the lower right of this image. Note the enigmatic “Grand Prizes” – they refer to those year’s World Fairs, at which the Graphophone itself (not the record) won a prize.

Now – what the heck is a Graphophone? It’s really no different from a gramophone or phonograph. The concept was identical, for the most part, to the phonograph originally developed by Thomas Edison. Competing scientists at the Volta Laboratory (founded by Alexander Graham Bell) refined and improved Edison’s machine by introducing a lateral recording method (instead of vertical cuts) and by replacing Edison’s impractical tinfoil-coated cast iron cylinder with wax-coated cardboard cylinders. Some authors breathlessly declare that it was Bell’s return fire against Edison; I think that’s a bit overly dramatic. Nevertheless the end result was no small improvement: “records” became less expensive, easier to produce, lasted longer, and offered much better sound quality. A trademarked name, the Graphophone moniker and the heavily patented technology was passed around by a series of company mergers and bankruptcies between the 1880s and the early decades of the 20th century, ultimately ending its usage in the 1930s as a Columbia disc brand. The technology itself spawned not only the laterally-grooved vinyl disc we are familiar with today, but also the Dictaphone and similar recording devices.

The piece “Babbling Brook” is by the composer Charles W. Rega. Stop reading this for a second, open another tab and head to Google. Enter “Charles W. Rega” and hit search. That’s about as much as I could find about Rega, too.

After checking hard copy references I could still find no reference to a Charles Rega ever existing in this period (except one: Charles Rega was a lay reader in the village of Skaguay, Alaska as part of the Alaska Missionary District in 1895 – I doubt he also wrote songs). Then, a break-through. Brooks’ Columbia Master Book Discography does include a listing for “Babbling Brook” and the master number matches exactly with the one on this record: 39064. It is the same exact song, but in the Discography the composer is listed as “Milo Rega.” Aha. Milo Rega was the pseudonym of Fred Hager (1874-1958).

Hager is best known as one of the first “A&R” guys. He and his colleague Justin Ring were scouts for Okeh records in the 1920s and assembled the group that backed black singer Mamie Smith in some of the recordings that many blues buffs consider the foundations of the “Race record industry.” Okeh would go on to become one of the leading labels for early blues musicians. Hager’s instincts were rooted in his own musical abilities. Starting in the 1900s he wrote songs for the Zonophone (a label founded in 1899 and shortly sold to, yep, Columbia, who affiliated it with its other alternative label Oxford). Hager and Ring worked together on compositions into the 1920s, many of which were credited to the fictitious F. Wallace Rega, Miles Rega, or Milo Rega, aliases derived from Hager’s own name. I cannot find any other reference to his using “Charles W. Rega” but the composer of “Babbling Brook” is almost certainly Fred Hager. A search for Hager’s name in connection with “Babbling Brook” confirms this: in February 1922 Nathan Glantz directed the Xylo Novelty/Specialty Orchestra in a recording of the piece, credited to Hager by name, that appeared simultaneously on Banner Records 1083 and Regal Records 9207. Interestingly, Glantz also directed the “Rega Dance Orchestra” on Okeh Records. Here, however, is the earlier Columbia A-1485 recording of “Babbling Brook” from my collection.

I almost titled this post “Bait and Switch” because when I first picked up this record it was the composer’s name on the B-side that caught my eye: Holst! A Holst song from circa 1913 would immediately precede the famed composer’s most acclaimed work – “The Planets.” Perhaps the “The Village Belles” would provide some taste of the almost hymn-like orchestral masterpiece, an early testing of the resounding bells that fill Gustav Holst’s Opus 32 masterwork (if you listen to it, it clearly does not). I hit the books, but could find no piece – not even a movement within a larger piece – titled “The Village Belles” by Gustav Holst. Thinking it may have been a different title wrongly ascribed to another Gustav Holst piece I listened to his works from the 1910s and 1900s to find a match. No luck. I searched for instrumental works with that title from the period and found reference to a piece with that title by a T.E. Spinney in the 1884 edition of The Monthly Musical Record and in the library of Victorian era English tenor Sims Reeves. The Reeves connection, and a discovery that Spinney also wrote a Te Deum, among other works for vocalists, suggested that his piece “Village Belles” was likely also a piece for vocalist. That and the 1884 date discouraged me from considering this song to be Spinney’s.

Then I stumbled across the other, lesser known but more prolific Holst: Eduard.

Eduard Holst was born in Copenhagen in 1843 and was an exceptionally productive composer, dance master, playwright, and occasional actor. Most of his over 2,000 works were songs and solo piano works, the most popular of which were probably his “Dance of the Demons,” “Beautiful Evening Star,” and “Diana Grande Valse de Concert” – a piece arranged variously over the years for 2, 3, and 4 pianos (that’s 4, 6, or 8 hands).

Little else is known of Eduard today, despite his lengthy roster of compositions and his copious output. He died in New York City at the relatively young age of 56. Assuming he started composing when he was 20, that’s 2,000 pieces over 36 years – or an average of about 56 compositions a year, almost five pieces per month every month of his life. In his time Eduard Holst’s piano music was so inexhaustible that one publication included it in a “Litany” that is well worth posting in its entirety:

A LITANY: CANTO II From wedding invitations and from the history of the United States; from the piano pieces of Eduard Holst and from fat women who are afraid of being betrayed; from all plays that run on Broadway more than fifty nights and from the Emmanuel Movement; from female bachelors of arts and from physical exercise in all its hideous forms; from editorials in newspapers and from the theory that it is sinful to chew tobacco; from the streptococci and from serial novels; from denaturized [sic] alcohol and from chilblains; from the works of Henryk Sienkiewicz and from chicken salad; from ecclesiastics who essay to be jocose in the pulpit and from the initiative and referendum; from fresh water oysters and from labor leaders; from theosophy and from the genealogical page in the Boston Transcript; from Uncle Tom’s Cabin and from elderly ladies who sit on the piazzas of summer hotels and swap obstetrical anecdotes; from bier jisch and from glassy potatoes; from perfumed cigarettes and from remorse from the doctrine of infant damnation and from Rosa Bonheur’s “The Horse Fair” – good Lord, deliver us! (The Smart Set: A Magazine of Cleverness, Volume 37, 1912).

Give the type and style of music Eduard Holst composed, the years in which he was most active, and the style and sound of this song on Columbia A-1485 (a gavotte is a type of French dance from the mid-19th century) I am quite confident in saying that “The Village Belles” is the work of Eduard Holst, not Gustav. Here is, as far as I can find, the only audio recording of “The Village Belles” by Eduard Holst available today.

The “Prince” in Prince’s Orchestra and Prince’s Band refers to Charles Adams Prince. Prince, said to be a descendant of Presidents John Adams and John Quincy Adams, was an accomplished pianist and organist, cutting his first recording in 1891 for the New York Phonograph Company and making his way, eventually, to Columbia, where he accompanied on the first Columbia Grand Opera Records through 1902. In that year, Columbia’s orchestra director – Fred Hager (that’s right) – stepped down from the post and Prince was named to fill the spot. Three years later Prince’s Band (or Prince’s Orchestra, largely depending on the instrumentation called for with each piece) was formed at Columbia. He would serve as the director of various Columbia house bands and his own eponymous one until 1923 when he changed labels to Puritan Records and, finally, Victor Records, to serve as associate music director.

Most jazz aficionados are familiar with the Prince’s Band recordings as they are often the first recordings of some true classics of the genre. Their 1915 rendition of W.C. Handy’s “St. Louis Blues” is one such record, as are their recordings of Porter Steele’s “High Society” in 1911 and Lew Pollack and Ray Gilbert’s “That’s A Plenty” in 1914 (a song that was, incidentally, a standard part of this author’s repertoire when he played in the band Lookin’ For Treble in the late 1990s). The Prince’s Band recording of Handy’s “The Memphis Blues” in 1914 was preceded by the initial recording – by the Victor Military Band – by only one week. In addition to these jazz classics in 1917 the versatile Prince conducted Richard Wagner’s “Rienzi Overture” for what was Columbia’s very first classical music release.

Prince’s Band/Orchestra was made up of some of the top instrumental talent of the day. Most of these men can likely be heard on this particular record: Vincent Buono (cornet), Leo Zimmerman (trombone), George Schweinfest and Marshall P. Lufsky (alternately flute and piccolo), Arthur Bergh and George Stehl (violin), Thomas Mills (xylophone, bells), Howard Kopp (xylophone, bells, drums), Thomas Hughes and William Tuson (clarinet), and Charles Schuetze (harp). While they primarily backed vocalists for Columbia, often without label credit, the band itself had a remarkable 80 instrumental recordings in the Top Forty hit charts between 1905 and 1923, including three #1 hits: “Ballin’ The Jack” in 1914 and “Hello, Hawaii, How Are You?” and “The Star-Spangled Banner” both in 1916.

For the return of Zayde’s Turntable I wanted to go back to the original spirit of this blog and the project that inspired it: to select a record at random from my collection, research it, record it digitally, and share it. When I pulled Columbia A-1485 out from the middle of the stack I was very happy to find the name Holst on one of the sides. Knowing the Columbia label was from around the time period of “The Planets” I got ahead of myself and thought it was Gustav Holst. It took several days of research for me to piece together the truth – though it would have been nice if Columbia had used a first name for the composer, as they did on the other side, or at least a first initial. Then, when I set to work on the reverse side I was flummoxed by the non-existent Rega. Even searches for pseudonyms of Charles Rega were fruitless. A careless typo led me to Milo Rega and then to Fred Hager. It’s not the first time I discovered a pseudonym on a record and, indeed, they were exceptionally common throughout the 20th century of recording.

Still, when I started on this post, I thought it would be a simple one to research. But even the simplest look record on the surface may have an interesting historical mystery beneath. I am quite pleased to place online a recording of Eduard Holst’s “The Village Belles” that – to my knowledge – not only does not exist in audio format anywhere else, but has been lost to history as a song that he even wrote. Given his current obscurity and the volume of his work, of course, that’s not a real surprise. I’m also happy to have been able to connect the enigmatic Charles Rega with Fred Hager. The early Columbia A-series was known for having a sometimes odd combination of songs on a record or in a series of records. A-1485 is two instrumental pieces, sandwiched in the catalog between two other styles of music, and representing two very different – but equally mysterious (and strangely, at the same time, equally prolific) – composers. It may have been a bait and switch, but I have to say that I’m satisfied with the outcome.