This week’s entry on Zayde’s Turntable: the first platinum film album in American history, featuring two extremely popular songs from an early 20th century feature, performed by an artist called “the world’s greatest entertainer.”

The record is a Brunswick label. Brunswick records were issued starting around 1916 by the Brunswick-Balke-Collender Company of Dubuque, Iowa, as an after thought to their line of phonographs. Brunswick was an early adapter of the lateral cut system and, thanks to an aggressive marketing campaign by the company, Brunswick records were in the “Big Three,” along with Victor and Columbia, for a number of years. Their acoustically recorded records were among the highest quality of the period, but the company made a miscalculation with the advent of electrically recorded albums. In 1925 Brunswick introduced their electrical recording technology, which they called the “Light-Ray Process” (it utilized photoelectric cells).

The audio quality was dismal, the records flopped, and hundreds of recordings made using the new system were never issued. In time Brunswick’s engineers were able to improve the failures in their recording technologies and the company moved quickly to attempt to recover the market share they had lost to Columbia and Victor in the interim. It was around this time that the Chicago-based label released some of their most acclaim albums (including this one) from their leading artists – Al Jolson, Duke Ellington, Ben Bernie, and more. The two genres that Brunswick became especially known for in this time was their “race series” of cutting-edge jazz, urban and rural blues, and gospel performances, and their very highly regarded classical music recordings of some of the leading orchestras and conductors of the era, including Toscanini. In 1930 the company sold the Brunswick label to Warner Brothers, who planned on utilizing it for film soundtrack recordings employing a “sound-on-disc” system they called Vitaphone. The combination of the industry standard shifting to the sound-on-film system and the Great Depression resulted in Warner Brothers’ decision to sell the brand to the American Record Corporation. ARC elevated Brunswick to their flagship label, selling the records for 75-cents, compared to 35-cents for their other brand records, and reserving the label for their biggest artists: Bing Crosby, Cab Calloway, the Mills Brothers, Duke Ellington, and others. In a convoluted industry deal ARC transferred the brand partially to CBS – who discontinued it in 1940 – and partially to Decca, which used it to release previous recordings and new records of rock and roll and rhythm and blues titles. The label finally “died” in 1982 following legal troubles. In the course of its lengthy life, Brunswick released about 67 different 78-RPM labels worldwide.

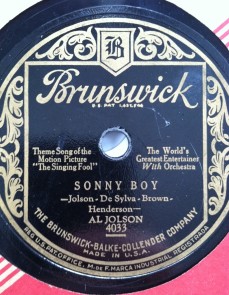

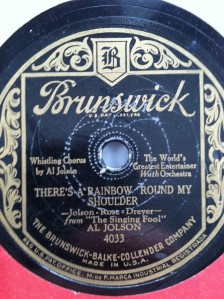

This album is in Fair condition; it has a slight dip that bulges the record slightly near one edge. Such bulging is not uncommon and often occurs from improper storage, excessive heat, or a combination of thereof; there is a technique to fix a warped disc like this – it involves a low-temperature oven, the flat back of a cookie sheet, and a very stead hand; I have not attempted it with this album and I do not intend to. The warp results in a distinct repetitive fluctuation in the music, especially on the A-side track. It is an acoustically recorded 10-inch diameter 78-RPM black vinyl disc with lateral grooves and a ¼” spindle hole. The record catalog number is Brunswick 4033. The A-side recording features “The World’s Greatest Entertainer With Orchestra” Al Jolson (1886-1950) singing “Sonny Boy,” the “theme song from the motion picture ‘The Singing Fool.’” The song was written by Jolson, George “Buddy” DeSylva (1895-1950), and Ray Henderson (1896-1970), with lyrics by Lew Brown (1893-1958). The track runs 3 minutes and 6 seconds. The B-side recording is Jolson again, including a “whistling chorus” by the performer (listen to the link to the full song, not just the clip below, in order to hear Jolson’s impressive whistling), in the song “There’s A Rainbow ‘Round My Shoulder,” also from The Singing Fool. “Rainbow” was written by Jolson, Billy Rose (1899-1966), and Dave Dreyer (1894-1967). It runs 2 minutes and 36 seconds. The album was recorded on August 20, 1928, the same year The Singing Fool was released. Brunswick 4033 was the first record of a film song in history to sell more than one million copies. It is one of a rare handful of albums that were recorded by popular artists – who are still popular or famous today – and were tremendous hits and that are of some monetary value (albeit slight, as is true for most all 78-RPM records, even the most collectible). Les Docks values it at $7-$10 and there are two dealers selling it on EBay for $5, one more at $10, and one at $11.

Born Asa Yoelson in Russia, Al emigrated to America in 1894 with his family, settling outside Washington, D.C., where his father was a rabbi and cantor. After his mother’s death that same year, Asa and his brother Hirsch began singing for coins on street corners using the Americanized names Al and Harry. In 1902 he joined Walter Main’s Circus, initially as an usher, but was soon given a singing role. When the circus folded in 1903 Jolson picked up a part in the burlesque show Dainty Duchess Burlesquers. When the burlesque show also folded within a year Jolson decided to put together his own act, forming a vaudeville partnership with his brother Harry. It was as part of their act that, in 1904 while performing in Brooklyn, that Jolson decided to try wearing blackface as part of his act; it was a tremendous success, but the act fell apart after Harry and Al had a falling out and Al struck out on his own in 1906. From there Al found success as a solo blackface vaudevillian, performing in San Francisco and New York. It was on stage at the Winter Garden Theater in New York in 1911 that Jolson truly became a celebrity, with an unbroken string of box office smashes, the distinction of becoming the highest paid performer in show business by 1920, and, at the young age of 35, his very own theater on Broadway – making Jolson the youngest man in American history to have a theater named after him. Jolson’s acts consisted of both songs and comedy, but it was the musical portions that largely built his recording career. His initial contract, with Columbia, resulted in several dozen top selling records, but it was after he left for Brunswick in 1924 that he recorded the album featured in this week’s blog post. His Columbia recordings were largely of his theatrical songs; when he retired from the stage in 1926 and began focusing more on film his recordings likewise changed, so his Brunswick albums consisted more of his film songs.

Jolson has been called one of the most influential and important singers and performers in American history. His stylings and performances of jazz, blues, and ragtime standards and new songs alike had a significant influence on later singers of the 20th century, including Bing Crosby, Judy Garland, Bob Dylan, Jackie Wilson, and even Jerry Lee Lewis, among many, many others. He was, without question, the most famous – and highest paid – American entertainer of the 1930s. Even before his largest smash hit, the film The Jazz Singer, in 1927, and his tremendous successes of the 1930s Jolson had already released, since 1911, 80 hit records, conducted 16 national and international tours, and sold out nine shows at the Winter Garden in a row. The brash, extroverted performer was known for his highly sentimental, almost melodramatic approach to songs. Jolson was the first performer to actively engage with his audience when performing, using a stage runway that ran out into the audience, which he would run up and down and perform upon, often singing to specific individuals in the audience. It was a new style and one that would lay the foundation for both the modern American musical and rock icons like Elvis Presley, who would later adapt Jolson’s performance techniques and “character”.

Jolson performing in blackface in the film "The Jazz Singer" (1927). He had employed the makeup for nearly twenty years by that point as part of his vaudeville act.

Interestingly it was in his blackface performances that Jolson truly stood out as a talented performer and they were, by his own account, some of his most enjoyable performances. Unlike other blackface actors of the period, however (such as Billy Golden and the Kaufman brothers, whom I have discussed in previous posts), Jolson’s blackface act did not lampoon or satirize black people. Rather, by bringing a simultaneously dynamic and sensitive approach to his blackface act Jolson felt he was at once celebrating the true energy and spirit of jazz and blues music and liberating himself as a performer to truly become a whole new person. Indeed Jolson has been credited with leading the fight against anti-black discrimination on Broadway from as early as 1911 and his efforts helped make possible the careers of such black musicians as Cab Calloway, Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Fats Waller, and Ethel Waters. Growing up Jolson was a close friend of Bill “Bojangles” Robinson and in 1911, at the age of 25, he helped black playwright Garland Anderson produce one of Anderson’s works, which became the first play with an all-black cast ever produced on Broadway. After his fame, and clout, grew, Jolson pushed to feature all-black dance troupes in his stage act and fought for equal treatment for Calloway when the two performed together in the film The Singing Kid. It was even said that there were black nightclubs in Harlem to which no white would be admitted – except Jolson. When Jolson died countless black actors lined the funeral processions and Noble Sissle, president of the Negro Actors Guild at the time, attended the funeral on the group’s behalf. Jolson’s blackface act helped bridge a cultural gap between white and black America by introducing black musical stylings such as jazz, blues, and ragtime, to white audiences.

Most music historians think one of the key facets that made Jolson’s blackface performance disarmingly non-offensive was that it was, whether intentional or not, an illustration of the mutual suffering shared by both blacks and Jews in America. The metaphor of the Jewish entertainer donning blackface was not lost on contemporary observers of Jolson’s work. For example, after seeing Jolson’s stage show, the writer Samson Raphaelson said “My God, this isn’t a jazz singer. This is a cantor!” From that image Raphaelson penned the story of The Jazz Singer, Jolson’s largest hit film and the first full-length picture with sound, in which Jolson portrayed the son of a cantor who wants nothing more than to become a jazz singer. One film critic astutely reflected:

“Is there any incongruity in this Jewish boy with his face painted like a Southern Negro singing in the Negro dialect? No, there is not. Indeed, I detected again and again the minor key of Jewish music, the wail of the Chazan, the cry of anguish of a people who had suffered. The son of a line of rabbis well knows how to sing the songs of the most cruelly wronged people in the world’s history.”

Black audiences responded to The Jazz Singer with acclaim. A crowd at the Lafayette Theater in Harlem wept during the film and the Harlem newspaper Amsterdam News raved of Jolson that “every colored performer is proud of him” and of the film that it was “one of the greatest pictures ever produced”

Jolson would return to the concept of a shared oppression between Jewish and African American peoples, especially in terms of how they suffered in a new land, in his film Big Boy. Jolson, in blackface, plays a former slave who leads a group of recently freed slaves (all played by black actors) in the slave spiritual “Go Down Moses.” One contemporary critic of Big Boy keenly observed:

“When one hears Jolson’s jazz songs, one realizes that jazz is the new prayer of the American masses, and Al Jolson is their cantor. The Negro makeup in which he expresses his misery is the appropriate talis [prayer shawl] for such a communal leader.”

Jolson performing for American troops in Korea in 1950. The trip would exhaust the performer and lead to his death at 64 that year.

Jolson, who was politically conservative – a rarity amongst Hollywood and Broadway stars, especially Jewish entertainers – was keenly interested in supporting America’s fighting men. As early as 1922 he held a hugely successful benefit performance at the Century Theater in New York, with the proceeds raised going to aid Jewish veterans of World War I. During World War II he was the first major star to travel abroad to entertain the American troops and, during the Korean War, he went overseas to perform for the troops again. The trip to Korea – 42 shows in just over two weeks – was grueling and, just a few weeks after returning to the U.S., he died from the exertion. As a result of his service to the troops the U.S. military awarded him (posthumously) the Medal of Merit.

The Singing Fool (1928) held the box office record for attendance for 10 years, when it was broken by Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Its worldwide gross of $5.9 million made it Warner Brothers’ most financially successful film for 13 years, until 1941’s Sergeant York. The Singing Fool, produced by Warner Brothers, solidified both the idea of sound in film as a standard practice from that point forward (many audiences were forced to watch The Jazz Singer without sound as few movie theaters were equipped to play any sound in 1927) and advanced the genre of musical film in general. However The Singing Fool, like The Jazz Singer, was actually only partially synchronized with recorded music and spoken dialogue – Jolson’s first all-talking film, Say It With Songs, would be released in 1929 – and in some places was even released and shown as a completely “silent” film.

Jolson and Davey Lee (as Sonny Boy) in a promotional still from the film that became an iconic image of the movie and later was used on the cover of the novelization of the film's story.

In addition to “Sonny Boy” and “There’s A Rainbow ‘Round My Shoulder,” the next most famous Jolson tune from The Singing Fool is arguably “I’m Sittin’ On Top Of The World.” Many of the songs from the film were tremendous hits when sold on record, piano role, or sheet music. It was an all-around commercial triumph for Jolson and for Warner Brothers. In the film Jolson plays Al Stone, a struggling singing waiter. Stone finally gets his big break when, on one night, his performance wows a big-shot producer and the showgirl that he fancies. Stone is catapulted to stardom, marrying the gold-digging girl and finding Broadway success. In typical melodramatic form, however, fame does not bring Stone happiness: Stone’s fickle wife leaves the performer, taking their son, whom he calls Sonny Boy, with her. The heartbroken singer falls from stardom and must rely on his old friends from the speakeasy where he got his modest start to save him from a dismal life on the hard streets.

“Sonny Boy” was the first song from a movie to sell over a million copies, eventually topping over 3 million copies sold of its record, piano roll, and sheet music (the first record of any type to break the 1 million mark was an Enrico Caruso album from 1904). The Brunswick recording held the #1 spot on the U.S. charts for an impressive 12 weeks. The heavily melodramatic tearjerker, sung by Jolson to his son in the film, has had surprisingly few covers since his 1928 recording: the Andrews Sisters cover of the song in 1941 reached #22 on the charts and a 1955 Arlid Andresen version, on piano, guitar, and bass, appeared in a medley of melodies released on the His Master’s Voice Label.

“There’s A Rainbow ‘Round My Shoulder”, “Sonny Boy,” and “I’m Sitting On Top Of The World,” were the three biggest hits of The Singing Fool. Jolson had a hand in the composition of “Rainbow” and it became one of his more recognizable trademark tunes and a staple of his stage performances and his shows abroad for U.S. troops. Among other artists to cover the tune were Donald Peers, with dual pianos, in 1949, which was released on His Master’s Voice, and Bobby Darin, who recorded a version in 1962 that was released by Capitol Records.

There’s a lot that could be written about Jolson – about his personal life and relationships, his works, his influence of later performers, his use of blackface, his pioneering work to bring sound into the movies, his efforts to advocate for and defend black entertainers and musicians when it was socially and professionally risky, and even his role in U.S. politics and presidential campaigns. If you would like to find out more about the “world’s greatest entertainer” (if not perhaps one of its most important), there are many other outlets online and in print to do so. I’m immensely pleased to have this and a few other Jolson records in my collection – indeed, I cannot imagine any library of important, or even standard, recordings from the early 20th century of American music, could considered complete without some of these Jolson classics. I’ll simply close with a quote from Jolson’s friend, the actor George Jessel, who was speaking the eulogy at Jolson’s funeral in 1950 after the 64 year old singer had died.

“The history of the world does not say enough about how important the song and the singer have been. But history must record the name Jolson, who in the twilight of his life sang his heart out in a foreign land, to the wounded and to the valiant. I am proud to have basked in the sunlight of his greatness, to have been part of his time.”