Last week Zayde’s Turntable featured a record that captured perhaps one of the most culturally sophisticated and artistically profound albums in my collection. This week we turn to the opposite end of the spectrum, with a performance, while no less culturally important, of a far baser nature.

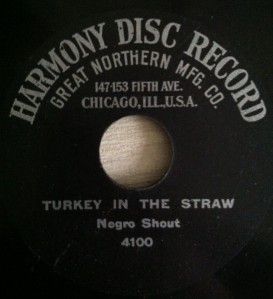

Harmony Disc Records (HDR) were manufactured in Chicago by the Great Northern Manufacturing Company starting in 1907. The label was discontinued after a merger of several labels in 1916 that formed the Consolidated Talking Machine Company, making this disc one of the oldest (though not the oldest) in my collection at probably around 100 years in age.

A Great Northern Manufacturing Company phonograph. The trumpet is probably not original to the machine. Note the large spindle pin in the middle of the turntable.

HDR albums are most notable because of their unusually large spindle hole in the middle of the record (at ¾” in diameter the hole is 200% the size of most 78-RPM records); this suggests the records were made specifically to play on a precise machine, one made by – you guessed it – the Great Northern Manufacturing Company. Kind of like how cell phones today can only plug into the charger manufactured by their company. Infuriating. HDR was not the only label to employ the extra-large spindle hole. Standard (at 1/2” diameter), United (1/5”), and Aretino (3”!) did likewise. All four of these labels were brands of the Great Northern Manufacturing Company and there are some instances reported of records in which two of these labels appeared on one disc, one on each side.

Great Northern sold their phonographs for a fraction of the cost of competitors’ machines (sometimes even giving them away): compare $1 for a Great Northern phonograph to $30 for a comparable machine from Victor. The cost savings are obvious, but once the customer was locked into the Great Northern machine, they could only play that company’s discs because of the spindle size. Again…this all sounds somewhat familiar. Sadly, some Great Northern owners reportedly went so far as to take drills or files to ¼” spindle hole discs to get them to fit on their Great Northern gramophone. The outcome of such an attempt can probably be guessed. Owners who later upgraded to a standardized ¼” inch spindle machine would likewise sometimes plug the holes of their Great Northern records to get a better fit.

Several labels had "Harmony" in their name, but they were not from the same company. The bottom image was a label that issued Christian Science recordings.

HDR should not, of course, be confused with Harmony records or the handful of other labels that employed the word “Harmony” in their brand name. The earliest HDR records (including this one) were one-sided issues and sold for four cents.

This album is in Fair condition, with the expected wear that would come from a record of such age. Despite its age, however, there are no significant scratches and the entire shellac is intact, though worn; the record is playable all the way through but the audio quality is poor (while I supply a clip below, I recommend following one of the links provided below to the full song available elsewhere online). It is an acoustically recorded 10-inch diameter 78-RPM black vinyl disc with lateral grooves and a ¾” spindle hole. The record catalog number is Harmony Disc Records 4100 and there is no master number. There is only one side of recording on this album; an unnamed vocalist accompanied by an unnamed pianist singing the “Negro Shout” “Turkey in the Straw.” It runs 2 minutes and 36 seconds.

The back of the record has no grooves or recording, indicating it was from the earliest days of recorded discs.

The precise record date is unknown, but it likely falls some time between 1901 and 1908 (the record’s use of only one side and its thickness suggest an album of this age, as later discs tended thinner and double-sided as technology and engineering improved). It does not appear in Les Docks’ valuation guide and there is no dealer I could find currently selling this exact record (some are selling a similar recording by the same artist on different labels: Columbia for $5, Victor for $10, Edison cylinder for $10, Edison disc for $11, an unidentified label for $36, and American Record Company for $115). The final two sellers seem a bit over the range of the rest and I would estimate the value of my record therefore to be in the $10-$15 neighborhood.

The label, unlike with many other HDR discs, is not printed on paper affixed to the album, but seems to be printed directly onto the shellac at the center.

A label affixed to the unpressed back of the record warns against duplicating or reselling the record (Megaupload, be warned!). It somewhat optimistically cautions that purchase of the record is accepting the condition that, if the record is sold below the price assigned to it by the company, it may not be played. Finally, it notes that the record may only be played on a phonograph that has the properly sized center spindle pin.

The warning label on the back of the record, with some numeric stamps on it, possibly prices or catalog numbers.

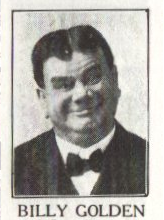

After some research I was able to determine that the vocalist on this record is the minstrel and vaudeville comedian Billy Golden (1858-1926). Golden’s performance of this song was issued on a multitude of labels, with all issues dating from within the first decade of the 20th century (American Record Company 30501, Victor 65, 17265, and 4515, Edison disc 50605, Edison cylinder 8293, Columbia A1291, and Monarch 65). And, of course, Harmony Disc Record number 4100 (click to hear the entire song on the HDR record elsewhere or below to hear a clip off my own copy of the record).

Golden was a prolific comic of the late 19th century and early 20th century. He started in the entertainment industry with a blackface spoken word act in 1874 and pressed his first record, for Columbia, in 1891. He would record with a multitude of labels as a solo act between 1891 and 1908, including as one of the first artists on the Berliner label (in 1895), eight titles for Edison, and a remarkable 51 records for Victor between June 1900 and September 1906. His three top records all placed in the top ten on the US charts the year they were issued (“Roll on the Ground” on Gramophone, his #2 selling record, placed 4th in 1901; “Turkey in the Straw” on Victor, his #1 selling record, placed 4th in 1905; and “Whistling Pete” on Victor, his #3 selling record, placed 10th in 1911). Fifteen of Golden’s recordings are available for a free listen through the Library of Congress’ National Jukebox. As a performer who specialized in the now highly insensitive and repugnant blackface routine, Golden (who was white, of course) has a roster of track titles that reads like a case illustration in the racially derogatory type of entertainment that was, unfortunately, for far too long a well-selling staple for the American music and comedy industries: “Turkey in de Straw,” “Yaller gal,” “Sisseretta’s visit to the North,” “Rabbit Hash,” “Roll on de ground,” “Crap shooting,” “Uncle Jefferson,” “In front of the old cabin door,” etc.

Blackface was a type of theatrical makeup and performance utilized, in America, during the minstrel show and vaudeville eras (from roughly 1830 to 1930), though its earliest recorded use dates as far back as the 15th century in Europe and blackface minstrel television programs in Britain persisted until as late as 1981. Blackface involved, for white performers, the heavy application of burnt cork and, later, grease paint or shoe polish, to darken the skin and exaggerate the lips; costuming would exacerbate the caricature and typically included wool wigs, gloves, and tailcoats or, with other common blackface “characters” (the cast of stock characters depicted was generally universal, similar to commedia dell’arte), ragged clothing. During the vaudeville period black actors who wished to take to the stage were even required to perform in blackface themselves. The blackface style died off finally with the successes of the Civil Rights movement, except for satirical uses and the occasional idiotic undergraduate costume party.

Billy Golden (right) with his post-1908 comedy partner Joe Hughes. Hughes was the straight man to Golden's buffoon.

Golden’s repertoire included singing solo and duet, comic monologues, comic scenes, and laughing and whistling solos. This album was probably popular because it was a well-known song and his performance of it included almost his entire repertoire: singing, monologue, whistling, and laughing. His blackface “character” was a stereotyped buffoon performed with “unrestrained glee and wit,” as well as “black dialect” (an important cue to the listener once the blackface act became audio-only on a record). In 1908 Golden teamed up with comedian Joe Hughes and issued a number of records performing a two-man blackface comic bit that laid the groundwork for the likes of “Amos and Andy” and other performers (including, more immediately, Jack and Phil Kaufman). Golden and Hughes performed to great success both on vaudeville and on records, with Hughes taking the role of the straight man and Golden the joker, complete with “crazy laugh and exaggerated dialect.” Their acts had such titles as “Darktown Eccentricities,” “Unlucky Mose,” “An Easy Job on the Farm,” “Hotel Porter and the Traveling Salesman,” “Aunt Mandy,” “Jimmy Trigger’s Return from Mexico,” “Love Sick Coon,” and “The Coon Waiters.”

Bizarrely, Golden can also be credited with an act that advanced and made possible the career of one of the most important record producers in the classical music genre. One of Golden’s piano accompanists for his Columbia and Berliner recordings was a young Fred Gaisberg (1873-1951). Golden thought Gaisberg was talented and helped the pianist receive a job as a recording engineer for the Gramophone Company. In that position in 1902 Gaisberg recorded a now famous and exceptionally important series of albums for Victor featuring the tenor Enrico Caruso (the opera singers first recordings and also the first records to be issued on the His Master’s Voice label). From there Gaisberg was catapulted into the upper echelons of the classical music and opera world and became, in a sense, one of the first major classical music producers of the recording age.

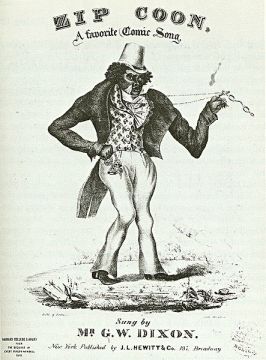

Sheet music to "Zip Coon," also called "Old Zip Coon," which was based on the tune for "Turkey in the Straw." Zip Coon was a blackface stock character.

The song “Turkey in the Straw” is one of America’s oldest minstrel tunes. The earliest references to the song seem to be around 1820, with its melody based on a fiddle tune called “Natchez Under the Hill.” The historical derivation of “Natchez Under the Hill” has been traced even further back to the ballad “My Grandmother Lived on Yonder Little Green,” which is itself derived from the Irish ballad “The Old Rose Tree.” It was first published with lyrics in 1834 under the title “Old Zip Coon” and became wildly popular during the Andrew Jackson presidency. That the song was, in its infancy, entitled “Old Zip Coon” and that a blackface vaudeville performer would sing it is no coincidence. Even as early as the mid 19th century blackface performers were singing the song, as its title was, in fact, a reference to one of the most common blackface stock characters, Zip Coon:

“First performed by George Dixon in 1834, Zip Coon made a mockery of free blacks. An arrogant, ostentatious figure, he dressed in high style and spoke in a series of malaprops and puns that undermined his attempts to appear dignified.”

As commonly happens with American folk songs the melody was appropriated for a variety of lyrical settings. The tune was set to songs about the American Civil War, obscenities, fishing, and even doggerel.

“Old Zip Coon” and Golden’s performance of it as ‘Turkey in the Straw” may clearly be classified as what musical historians have called “coon songs”: a heavily syncopated, fast-paced style of music (intended to mimic ragtime) commonly, though not exclusively, performed by blackface singers between 1880 and 1920 that – especially when accompanied by the blackface makeup, costume, and physical and vocal performances – portrayed blatantly racist and stereotyped images of blacks. “Coon songs” were a national craze at the end of the 19th century, with over 600 such songs being published in the last decade of the century alone – one of many signals that, despite emancipation, black Americans had a long, hard road still to travel. The genre included songs with such names as “The Dandy Coon’s Parade,” “The Coons are on Parade,” “New Coon in Town,” “Coon Salvation Army,” “A Trip to Coontown” (written by black composer Bob Cole), “Every Race has a Flag but the Coon,” “Coon Coon Coon,” and “All Coons Look Alike to Me.”

The lyrics to "Old Zip Coon" from a mid 19th-century document printed in Vermont. I've included it at the largest size possible to permit the text to be readable.

Quite a bit could be written about the history, rhetorical and racial significance, and sociological or psychological underpinnings behind the blackface and “coon song” movements in the American entertainment industry. And, indeed, quite a lot has been written on the topic. It’s easy to judge these repugnant chapters in our history now, in retrospect; on the other hand, we simultaneously patronize media that presents other stereotypical caricatures, including those of Muslims, Latinos, gays, Native Americans… You get the idea. There seems to be at once a murky line in some instances between what is cultural comment and what is intended to mock, stereotype, or demean. In other instances the line is bright and clear. Perhaps one of the clearest cues when something is crossing that line is the consideration of the intended audience. Blackface minstrel shows and “coon song” records were intended for consumption by an almost entirely white audience; the stock characters and stock storylines reinforced existing bigoted notions of how black people looked and how they behaved. They were designed to be commercially successful and the shortest route to that end involved catering to the lowest, most base preferences and emotions of the consumer.

“The Importance of Being Earnest,” written and first staged in Britain while America was at the height of the blackface craze, was also a commercial success (and still is today) and it, too, mockingly satirizes a specific type of person and social institutions (British aristocratic society and Victorian conventions). Yet it avoids crossing that line. Is it because the targets of Wilde’s satire were white people? No. I would suggest it is because his art challenged the audience to think critically; it conveyed a social message, whereas blackface performers abetted and exploited a racist attitude that was latent. One pushed the audience to examine their culture; the other enabled them to stay safely ensconced in their comfort zone. As repulsive as their beliefs might be, it said to the consumer that those beliefs were acceptable and shared by others. In the end, while both records are still here in their physical form, the trajectory of history has – rightly in my view – elevated the former of these performances and disposed of the latter. One might well wonder which entertainment artifacts from today will persist in 100 years and which will not. And then one might wonder why.