The last two featured records on Zayde’s Turntable were, I must confess, selected with a little bit of deliberate purpose on my part. I liked the dichotomy of the John Gielgud performance of Oscar Wilde opposite the Billy Golden racist portrayal of “Turkey in the Straw.” This week, however, I have gone back to my original concept for this blog and selected a truly random album.

Not surprisingly, having selected a record at random means the label of this record, Columbia, is one of the big three (Victor, Columbia, and Decca). The history of Columbia is far, far too long to delve in to here – it is, in fact, the oldest surviving record label still in existence. Briefly, it was founded by Edward Easton as the Columbia Phonograph Company in 1888, deriving its name from its original location in the District of Columbia. The company pioneered a number of critical advancements in recording technology, including “double-faced” records (albums with a song on each side) in 1908 and the internal-horn gramophone that, ironically, became associated more with their competitor, the Victor brand. The history of Columbia, as far back as 1894, is one of mergers, acquisitions, and receivership. In its current form today Columbia is a brand of the Sony Corporation and is most commonly known for its sister subsidiary of Sony, the broadcast television network Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS). Interestingly another Sony company, Columbia Pictures – the film studio – was originally not related to Columbia Records at all (it did issue records of its own, but on the Colpix and Arista labels). Columbia Records issued well over 160 different types and styles of labels on their 78-RPM records alone, so I will not be posting my usual picture of the variety of labels from one company. Sorry to disappoint.

This album is in Good condition, with some light scratches that do not prevent playability; unfortunately there is one exceptionally tiny but deep nick on the A-side track. It is an electrically recorded 10-inch diameter 78-RPM black vinyl disc with lateral grooves and a ¼” spindle hole. The record catalog number is Columbia Records 1833-D and the master number is 148483/148484.

The A-side recording features Ted Wallace and his Campus Boys backing up an unnamed vocalist singing the fox trot “Jericho,” written by Academy Award nominated songwriter Richard Myers (1901-1977) with lyrics by Leo Robin (1900-1984) who penned the words to the Oscar-winning Bob Hope tune “Thanks for the Memories” and did the lyrics to, among many other shows, “Gentlemen Prefer Blondes” (1949 and revived in 1995). ”Jericho” is the theme song from the 1929 motion picture “Syncopation.” It runs 2 minutes and 52 seconds. The unique Columbia code impressed on the record, 1-B-9, indicates that the recording was the first take, from the second mother, and ninth stamper – suggesting there were, at a minimum, 18,000 copies of this song pressed.

The B-side recording also features Ted Wallace and his Campus Boys backing up an unnamed vocalist singing the fox trot “I’ve Got a Feeling I’m Falling,” written by Harry Link (1896-1956) and the famed jazz pianist and composer Fats Waller (1903-1943), who (along with Louis Armstrong) would go on to make the song famous, with lyrics by the influential theater impresario Billy Rose (1899-1966). It runs 2 minutes and 54 seconds. The Columbia code on the record, 1-B-7, indicates that the recording was the first take, from the second mother, and seventh stamper – suggesting there were, at a minimum, 14,000 copies of this song pressed.

The record dates from May 8, 1929, around the same time the film “Syncopation” was released. There is one dealer currently selling the same record, in Very Good condition, at Venerable Music auctions for $3, though Les Docks values the album at $7-$10. Interestingly, the unnamed vocalist on this record appears to be none other than the prolific singing cowboy featured on a previous record on Zayde’s Turntable – Smith Ballew.

Ted Wallace and his Campus Boys was a regular Columbia house band. The highest they ever climbed in the U.S. charts was their top-selling hit, “Little White Lies,” written by Walter Donaldson, which reached the #3 spot in 1930. Ted Wallace was, of course, a pseudonym. The man behind the band was conductor and music manager Ed Kirkeby (1891-1978). Kirkeby was one of the first producers at Columbia to record jazz albums and was a close associate and manager of Fats Waller (from 1938 to Waller’s death in 1943). Kirkeby’s foresight in viewing Waller, rightly in my view, as one of the most important figures in American jazz, led to the preservation of a remarkable volume of documents and other archival items related to Waller’s life and career at the Institute of Jazz Studies housed at Rutgers University.

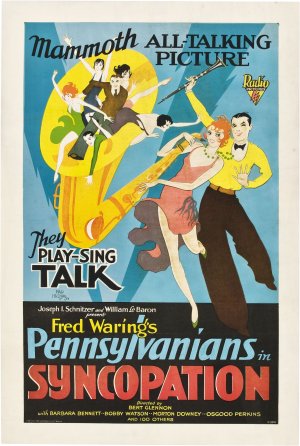

The song “Jericho” was originated by the exceptionally prolific bandleader Fred Waring and his Pennsylvanians in the film “Syncopation.” In the movie the song is performed by Morton Downey, with back-up vocals provided by the Melody Boys. In addition to the Waring version and the Kirkeby version, at least one other recording of the tune was made by Bidgood Broadcasters on Broadcast Record 413-A. In some sense, its placement on this record is a bit ironic: the song, written by two white men and performed by a white singer with a white band, is supposed to be “about jazz.” On the reverse of Columbia 1833-D, of course, we have a song written by one of the master’s of jazz, Fats Waller.

The song “Jericho” was originated by the exceptionally prolific bandleader Fred Waring and his Pennsylvanians in the film “Syncopation.” In the movie the song is performed by Morton Downey, with back-up vocals provided by the Melody Boys. In addition to the Waring version and the Kirkeby version, at least one other recording of the tune was made by Bidgood Broadcasters on Broadcast Record 413-A. In some sense, its placement on this record is a bit ironic: the song, written by two white men and performed by a white singer with a white band, is supposed to be “about jazz.” On the reverse of Columbia 1833-D, of course, we have a song written by one of the master’s of jazz, Fats Waller.

The musical film “Syncopation” was released in 1929 and was the second film produced by RKO Radio Pictures (though the first released by RKO). It was directed by Bert Glennon and starred Downey, Barbara Bennett, Bobby Watson, and Ian Hunter; the script was based on the novel “Stepping High” by Gene Markey. RKO was a company in the Radio Corporation of America (RCA) empire and they used the film to test their new “sound-on-film” process – a process that is still used today (in a slightly updated fashion, of course) by Dolby and all the other big names in movie sound. The 1929 film, and Markey’s novel, centers on two vaudevillians who are close both on and off the stage. One day a dashing millionaire shows up and starts to woo the female partner. She becomes smitten with the rich man and begins to needle her partner about his musical and personal faults. Sounds like a heart-warming tale, I know. IMDB users rate it 7.9 out of 10.

“Syncopation” was, in some ways, not a far ways distant from contemporary pop culture entertainment. I referred to it somewhat in jest in the title of this post as being similar to “American Idol,” but it is not precisely identical. The concept of the consumer/viewer being involved in the crafting of entertainment is the same. Not with the 1929 version of the film, however. Here also the movie is similar to what we see today for in 1942 RKO “rebooted” their 1929 movie. The kept some elements of the plot – a romance between singer Kit Latimer of New Orleans and Johnny Schumacher, in which they argue over and demonstrate the various styles of popular music (ragtime, jazz, swing, and blues). Hilarity and musical numbers ensue. In the 1942 version they updated the plot to cover music released between 1929 and the outbreak of World War II (most notably boogie-woogie). RKO also added another element, however: they held a contest for the readers of the Saturday Evening Post to vote by mail on the musicians who would make up the “All-American Dance Band” that appears in the film (in the 1929 version this was Fred Waring and his Pennsylvanians). The resulting musical ensemble was something of an all-star band for the era: Benny Goodman, Charlie Barnet, Harry James, Jack Jenney, Gene Krupa, Alvino Rey, Joe Venuti, with singer Connee Boswell. Of course, unlike “American Idol,” these artists were already famous – and they were voted on, not off.

“I’ve Got a Feeling I’m Falling” was a wildly popular song first published in 1929 and recorded by dozens of artists, including Fats Waller himself; several of the recordings can be found online. Ironically, while “Jericho” has faded from the annals of jazz history, “I’ve Got a Feeling I’m Falling” quickly became a key number in it. In 1929 alone I identified eighteen different records with the song including (in addition to Waller on Victor and the Ted Wallace on Columbia) Gene Austin on Victor, Smith Ballew again on Okeh, the Continental Dance Orchestra on Oriole and Jewel, Jesse Crawford playing an organ instrumental version on Victor, Gay Ellis and Annette Hanshaw on Supertone, Diva, Harmony, and Velvet Tone, the Gotham Rhythm Boys on Jewel, Harold Lambert on Vocalion, Sam Lanin’s University Orchestra on Supertone, Miff Mole and his Little Mollers on Okeh, Joe Morris on Champion, Ben Bernie and Scrappy Lambert on Brunswick, The Mystery Girl on Columbia, Willard Robinson on Columbia, and Cliff Roberts on Romeo.

“I’ve Got a Feeling I’m Falling” was a wildly popular song first published in 1929 and recorded by dozens of artists, including Fats Waller himself; several of the recordings can be found online. Ironically, while “Jericho” has faded from the annals of jazz history, “I’ve Got a Feeling I’m Falling” quickly became a key number in it. In 1929 alone I identified eighteen different records with the song including (in addition to Waller on Victor and the Ted Wallace on Columbia) Gene Austin on Victor, Smith Ballew again on Okeh, the Continental Dance Orchestra on Oriole and Jewel, Jesse Crawford playing an organ instrumental version on Victor, Gay Ellis and Annette Hanshaw on Supertone, Diva, Harmony, and Velvet Tone, the Gotham Rhythm Boys on Jewel, Harold Lambert on Vocalion, Sam Lanin’s University Orchestra on Supertone, Miff Mole and his Little Mollers on Okeh, Joe Morris on Champion, Ben Bernie and Scrappy Lambert on Brunswick, The Mystery Girl on Columbia, Willard Robinson on Columbia, and Cliff Roberts on Romeo.

Original 1929 sheet music for "I've Got a Feeling I'm Falling". Fats Waller uses his real name, Thomas Waller, here.

![Portrait of Ella Fitzgerald, Dizzy Gillespie, Ray Brown, Milt (Milton) Jackson, and Timmie Rosenkrantz, Downbeat, New York, N.Y., ca. Sept. 1947]](https://zaydesturntable.files.wordpress.com/2012/02/portrait-of-ella-fitzgerald-dizzy-gillespie-ray-brown-milt-milton-jackson-and-timmie-rosenkrantz-downbeat-new-york-n-y-ca-sept-1947-e1328301719533.jpg?w=151&h=180)

Ella Fitzgerald, with Dizzy Gillespie, in 1947, the same year she recorded a version of "I've Got a Feeling I'm Falling."

Ella Fitzgerald and the Daydreamers recorded it on Decca in 1947 and Earl Hines made two recordings of it, one for Signature in 1944 and a second for Brunswick in 1952. Other mid-century recordings include James P. Johnson on Decca in 1944, Art Kassel on Mercury in 1947, and Joan Shaw with Russ Case’s orchestra in 1950 on MGM. The song was included in the musical revue “Ain’t Misbehavin’,” which is a compilation of the music by Waller and other black musicians of the 1920s and 1930s who were so instrumental in the Harlem Renaissance. A 2008 revival of the play, featuring 2003 “American Idol” winner (oh, irony) Ruben Studdard, saw the song performed by Frenchie Davis.

In his 1983 film “Zelig” Woody Allen uses original footage of Fanny Brice singing the number on top of the Paramount Theater in New York. Allen edited the clip to splice in himself and Mia Farrow (the film is a fictional documentary in which Allen portrays a “human chameleon” who supposedly rubbed elbows with all sorts of famous people during the Roaring Twenties – kind of like a 1920s Forrest Gump). The original footage is available online and fun to watch, especially to see how Brice – a consummate performer – switches from her regular voice to her performance voice. In the clip Brice’s husband conducts the musicians – who is he? None other than Billy Rose, who penned the lyrics to Waller’s tune.

So, this week’s offering is a fun and up-beat album. I think it captures, in its own way, a touch of the state of American entertainment at the end of the Roaring Twenties, a time when the nation was poised, unknowingly, on the brink of some exceptionally hard and difficult times. But also, as suggested by both the songs on this record, on the brink of some of the most remarkable and important musical developments in the country’s history: the Jazz era.